There are a few works in music which inhabit some knife-edge between jubilation and tragedy, miraculously participating in both, but submerged in neither. Among these are Mozart’s Grosse Fugue and the final Hallelujah in the minor key in Bach’s cantata, Christ Lag in Todesbanden.

Brahms B flat piano concerto almost moves in this company. It is at once passionate and stoic, epic and intimate. It is very difficult for the soloist because it makes every technical demand yet the piano never holds the floor. It engages instead in an exalted dialogue with the orchestra.

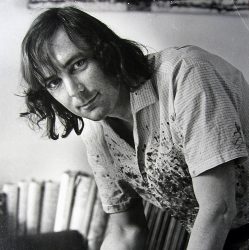

Ivan Melman gave an extraordinarily fine account of it last night with the Municipal Orchestra under Hugh Fenn.

It was a performance absolutely alive to the changes of mood, from the gropings of the opening, the turbulence of the second movement, the private musings of the andante, without ever losing the sense of the work’s structure.

Stimulus

The orchestra was at their very best, rising heroically to Brahm’s demands and making a moving surge of sound in the tuttis. Only the finale, with a missed entr and two inexplicable memory lapses by Mr. Melman, was disappointing.

The orchestra has been moved forward into the auditorium on platforms and has a new brightness and immediacy of sound. It means, however, that technical failures are not longer swallowed by the drapes and curtains. I suspect that this will be a stimulus to better orchestral playing. Certainly the orchestra gave an alert reading of Beethoven’s First Symphony, underlining mostly with precision this humorous flexing of the young giant’s muscles. Special credits are due for the pointing of the menuetto’s shifting accents and the tentative rising progression to the theme and the finale.