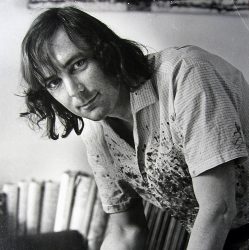

The oboe is one of the most obdurately difficult of the wind family to master. At 30, the Swiss player Heinz Holliger, who played in Bulawayo last night accompanied by Edith Picht-Axenfeld, is without doubt already a virtuoso of the first rank.

An enterprising programme exploited his brilliance and shrewdly. The repertoire is small, but he chose works which called not only on his extensive technical resources but also his ability to find a myriad of expressive nuances in an instrument which can easily sound monotonous.

The early F major Mozart Sonata and Donizetti’s in the same key showed the warmth of tone – Germanic, rather than the faintly acid tone quality most British players favour – and subtlety of phrasing

The Schumann Romances he played with greater emotional amplitude, helped here by the greater calls made on the lower registers of the oboe.

Question

Miraculous tonal control and imaginative projection made Britten’s Metamorphoses for solo oboe the highlight of the evening, which was nicely rounded off with Milhaud’s sly and pawky Sonatina.

Miss Picht-Axenfeld accompanied with total accord; neither too effacing nor too assertive.

Would the final Schumann Romance have hung together better if they had treated it less episodically, with greater rhythmic continuity?

That Miss Picht-Axenfeld is an artist of great distinction in her own right was clear in two Impromptus from Schubert’s Op 42. These were technically impeccable and touched the heart of Schubert’s emotional reticence. Her clarity of fingering, rhythmic play and quiet washes of tone, leading to an impressively stated climax in Debussy’s Estampes, completed and exciting evening well out of the usual run, both performance-wise and regarding choice of programme.