Marshall Baron & Stephen Williams Exhibition

Opening by Dr. Mike Gelman of Stephen Williams/Marshall Baron Exhibition in Bulawayo: September, 1975

In opening this exhibition of paintings by Stephen Williams and Marshall Baron I have been set my most challenging task since judging the Knitting Section at the Endeldoorn Women’s Institute Open Day.

It is challenging because the exhibition is an unusual one for Bulawayo insofar as the works on display are not only modern, but paintings of today, quite contemporaneous with those you will see at exhibitions in New York, London and Paris this week. The artists, both of whom opted for professions before taking to are – the first Accountancy, the second Law, show a fascinating contrast in style. One draws his inspiration from the contemplation of his own navel, the other by contemplating the navel of nature. Many of the paintings ask more questions than they answer. In fact, after a cursory examination, the only question I can see answered immediately is the reason for the current paint shortage in Bulawayo.

With so many intellectual challenges, it seems a strange choice that the artists should ask a simple country children’s doctor to open their exhibition, and I have grappled with possible reasons for their doing so. Firstly, it seems unlikely that the paintings are actually a risk in health, although if one of the larger canvases came unstuck it would be useful to have a doctor at hand. Secondly, although viewing the paintings may well produce adverse reactions in some, these reactions would surely not be severe enough to warrant the presence of a medical practioner. A stiff brandy or tow, 10 mg. of valium, or simply the balm of time should heal the damage. No, I am forced to conclude the reason for this invitation will be found in recent publicity from Parliament concerning the earnings of the medical profession. The artists must have reasoned that this singular compliment to our aesthetic taste would hopefully inspire me, and other prosperous medical colleagues, to indulge in art as a hedge against inflation.

Well, I’m sure we will not be taken in by this obvious ploy, and since so banal a choice of speaker was made, you must expect some equally banal remarks.

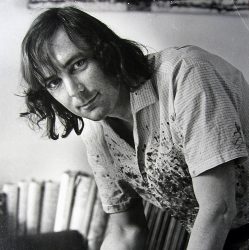

Let me first tell you something about the artists……

Stephen planned a career in accountancy, but suddenly started to paint quite seriously some six years ago. Interestingly enough, a Sunday afternoon’s session doodling on paper with Marshall Baron seems to have stimulated his interest in art…….

Marshall Baron , on the other hand, is a different case. His curriculum vitae is too well known to you to need repetition. His paternal lineage stems from Russian stock, along with the famous artist Ben Shahn, who was his father’s cousin. I have often been struck by the similarity in the careers and temperament of Marshall Baron and the Russian artist Vassily Kandinsky. Both practiced in professions for years before taking to art – Kandinsky in economics, Baron in Law. Both derived a great deal of inspiration from music. The mutually rewarding relationship between Schoenburg and Kandinsky is a fascinating story well worth reading. Urish Heap, The Bonzo Dog, and Doodah Band have had a similar effect on Baron. Like Marshall, Kandinsky was shy and uncommunicative, given to little speech; however, he would also fly into a towering rage if overcharged a rouble or two. Both very conservative in their dress, Kandinsky was never seen without his high wing collar, which he would even wear while taking a bath.

Kandinsky was, like Baron, most meticulous about little details…on one occasion it is said that while traveling from Moscow to Munich he alighted from the train at Novgorod and traveled all the way back to Moscow, a distance of some 2,500 kilometers, just to check that he had switched off the samovar. In one of his music critiques Marshall Baron once stated if Boticelli were alive today he would be working for Vogue, and Kandinsky’s writings express almost identical views. Another interesting similarity is that, like Kandinsky, Marshall takes his borscht by holding the bowl in the left hand and ritualistically dowsing the boiled potato three times in the fluid before eating it.

Baron has had five one-man shows of his work, one in Bulawayo and four in Johannesburg. He has participated in many group exhibitions in Bulawayo, Salisbury, Pretoria, and Skowhegan, USA. In 1966 he was awarded a full scholarship by the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. His work has been purchased by the National Gallery of Rhodesia. In 1972 he designed and executed original sets for the ballet “Nnogawuse”.

He has been Music Critic for the Bulawayo Chronicle since 1962. He writes brilliantly on music and art, and explains his own work with conviction. Sometimes one wishes he would explain his explanations. His paintings have the strange quality, in fact, of actually looking even better in the printed word than they do on the walls. Listen to some of these descriptions from critics: “….His delicate brush-work and subtle use of colour produce ethereal effects….” ….”meticulous design…” Oh sorry, that’s for an exhibition I’m opening next week. ….Here it is: “…a gleam of impish humour gives both depth and meaning to his curtomarily opaque style…” “….virility and vigour characterize this Rhodeain artist’s daring work….” “…an enormous apetitie for expressing himself….” “…his painting is so rebellious, purists might be outraged…” “he attacks his canvases like a swordman fighting for his life….”

Marshall has, in fact, become such an exhibitionist that some have even accused him of indecent exposure. His work tends to arouse strong emotions among his protagonists and his antagonists. But whatever the opinions are, Marshall in his paintings certainly has something to say, and he is saying it in a unique way. Like any work of art, a painting is one half of a dialogue, the other half of which is ourselves. I have evolved an approach in confronting a Baron work for the first time, which I commend to you. I suggest that you focus not on the formal details of colour and design, but force your eyes to penetrate through the paint to the canvas itself. Then carry on further, through the plaster and brick of the walls. Cross 9th Avenue, and pass the Farmers’ Coop. Keep going till the Shashi River comes into view. Stop there, and ask yourself these questions: How is this painting affecting me? How is it affecting society? What am I doing for society? What the hell am I doing at this exhibition? If you can find at least some of the answers to these questions, ladies and gentlemen, my opening remarks will not have been in vain.